Jemez Valley History Overview

This is a brief overview of the history of the Jemez Valley and surrounding areas from “the beginning of time.” See the timeline with details of events from 2500 BCE to the present.

Geologic Forces of The Jemez Mountains

Believe it or not, much of the area we now call “New Mexico” was once part of a vast inland sea. Sharks, rays, and other early marine animals inhabited the relatively warm waters for millions of years as the earth formed and landmasses settled. Today the remnants of volcanic activity still produce natural mineral hot springs that bubble up out of the ground in various locations throughout the Jemez mountains.

Approximately 1.6 million years ago, the area was essentially a giant “supervolcano” covering hundreds of thousands of acres and rising some 19,000 feet above sea level. Early eruptions laid down layers of iron-rich magma, now seen in the orange-red layer of iron oxide along the many arroyos throughout the Jemez range.

Another eruption 1.2 million years ago added thick layers of volcanic ash, called “tuff” that one can see today as the light beige layers nearest the top of the valley walls. What remains of the immense volcanic explosions is the Valles Caldera with its huge Valle Grande and a number of cinder cones. During all this time water, wind and sunlight worked on carving the rock into the spectacular mesas and canyons we see today.

Ancestral Puebloans

Humans have come to the Jemez Valley at least since 2500 B.C. The earliest visitors were undoubtedly seasonal hunter-gatherers. Later groups stayed long enough to harvest a corn crop, as evidenced by archaeological findings at Jemez Cave near Soda Dam. Over the millennia since then, groups migrated in, mostly from the Four Corners area, and eventually formed substantial pueblos. This habitation period culminated in a number of large pueblos. Remains of those ancestral sites are atop every mesa, many with hundreds of rooms. Archeologists’ latest estimates are that 6,000-8,000 people lived in the Jemez Mountains at the time of the first Spanish contact. The surviving Rio Grande pueblos are the descendants of a much larger population.

Spanish Settlers

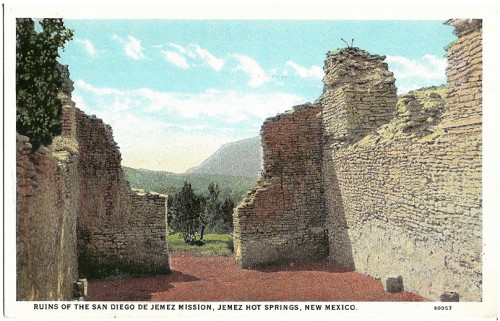

Recorded history begins when the Spaniards arrived in the area in 1541, nearly seven decades before the famed Jamestown settlement was founded on the East Coast. Each subsequent Spanish expedition sent out exploring parties, and subsequent visits to the Jemez were recorded in 1583 and 1598. In addition to searching for riches, the priests accompanying the exploring parties established missions. One of the most important of the mission churches built by the Franciscan Fathers in the 17th century was San Jose de Guisewa, now Jemez Historic Site just north of the Village of Jemez Springs.

The Spanish were expelled in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. They returned in force in 1692 and reconquered all of their previously occupied territory. The land gradually became repopulated by Spanish farmers, although only an estimated 300 Jemez returned, their numbers decimated by disease and hardship. A number of land grants were awarded by the Spanish Crown to Spanish colonists and Indian pueblos. The earliest of several grants in this area was in 1768.

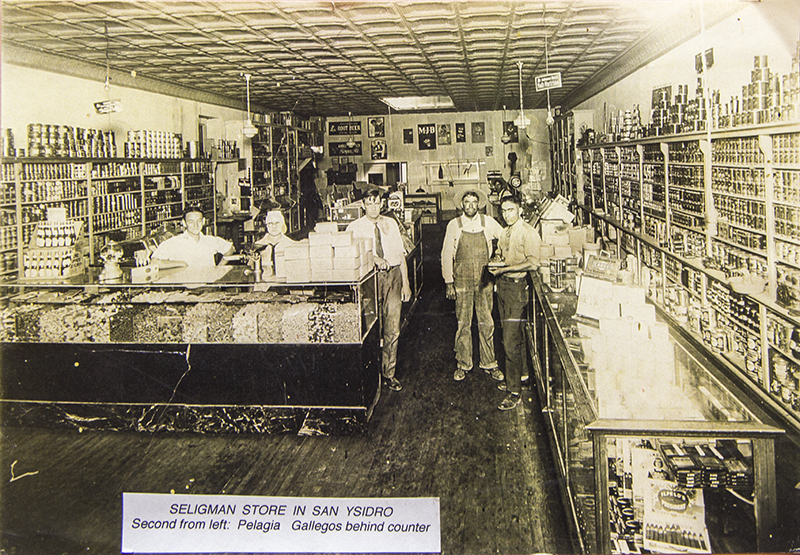

By 1821, the Spanish population numbered around 800, according to Spanish records of the time. During the 1800s, the area was at first solely occupied by farmers, then later sheepherders and ranchers. They continued to be subjected to raids from Navajos (an eastern boundary of the Navajo Nation lies just west of the Nacimiento Mountains). While many Spanish villages are long buried under dirt and dust, a surprising number have survived for more than 500 years. Oldest in this region are Sam Ysidro, first settled in 1699, and Cuba, settled by 1736. All were built in the traditional style around a plaza, and while some have retained that design, many have been distorted by modern highways and growth patterns. The Spanish settlers lived happily for centuries, herding sheep and cattle on their common lands, growing crops in the rich bottomlands along rivers and streams, worshiping in small churches that were the center of each community.

U.S. Takes Over

Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago, signed in 1848, Mexico ceded what became New Mexico and Arizona territories to the United States. With the arrival of the Americans, life as the Spanish pioneers knew it would never be the same. U.S. courts did not know what to do with the Spanish system of land grants and communal holdings. Many of the land grants became fractured. Eventually, the forest they all shared for grazing and wood gathering became a national forest with restrictions. Besides farming and ranching, logging and mining became the main industries until World War II. Two railroads were built to serve the logging companies. One ran from a sawmill in Bernalillo to Cuba, and the other into the forest along the Guadalupe River.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the villages in this area developed services and infrastructure. Cuba, San Ysidro, Jemez Springs, Ponderosa, and Cañon continued to develop and modernize, while others became solely residential enclaves or faded into ghost towns.

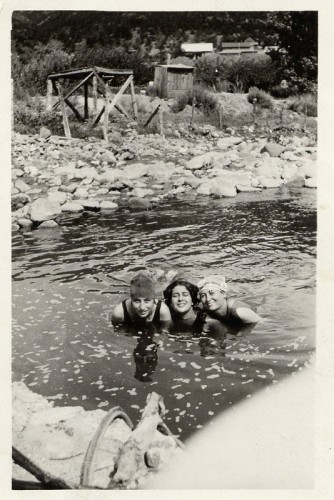

Jemez Springs had been a tourist destination since the 1800s because of the mineral hot springs, and that attraction drew people to the valley. Of course, local people had fished and hunted in the Jemez Mountains for centuries, but recreational hunting and fishing began to attract visitors as travel conditions improved. Surviving villages today lie on the edges of the mountains or along major valleys, served by paved state highways. However, even today local residents must drive to Los Alamos or Bernalillo (or on to Santa Fe and Albuquerque) to find a supermarket or hardware store, not to mention a mall. Because most communities are bounded by national forest or Indian reservations, land development has been held to a minimum. That and steep-sided mesas and deep arroyos put build-able land at a premium.

Jemez Mountains Today

Despite the dramatic changes of the last 150+ years, many old traditions live on in the people and places we see today. Public dances at Jemez Pueblo resemble those done for generations. Water still flows through acequias dug more than 100 years ago. Old adobe or river-rock-and-mortar buildings have stood the test of time. Descendants of some of the original families, those named on the old Spanish land grants, live here today.