Logging for fuel and building materials was an essential use on land held in common by early settlers on the Cañon de San Diego Grant. It was not until the 1920s that logging became a commercial enterprise. Logging companies were responsible for a railroad with two branches and several spurs that reached far into the Jemez Mountains. When mechanized vehicles replaced animals to haul timber to the railheads or mills, loggers cut innumerable roads through the mesas and valleys. Many of these have morphed into pleasant hiking trails with a gentle grade. Intensive logging on the Baca Location No. 1 in the 1930s resulted in clearcuts still visible today.

As typically happened on land grants throughout the Southwest, the twists and turns of the American legal system resulted in the loss of much of the common land, mostly to unscrupulous lawyers and the U.S. government. In 1904, the Cañon de San Diego Grant was sold to the Jemez Land Company. (See Land Grants for the history of land grants in their area.) In 1920, the earlier idea of a railroad up into the Jemez was revived, this time not for tourism but for access to the resources of coal, copper, timber, and sulfur. The first plan for the Santa Fe and Northwest Railroad was to lay track right up the valley along the Jemez River. That idea was later modified, and two branches were built from San Ysidro. One ran up through Guadalupe Canyon, with spurs extending as far north as Cebolla Creek (which now feeds Fenton Lake). The second was constructed roughly along the route of today’s Hwy. 550 to La Ventana, a long-abandoned mining town south of Cuba.

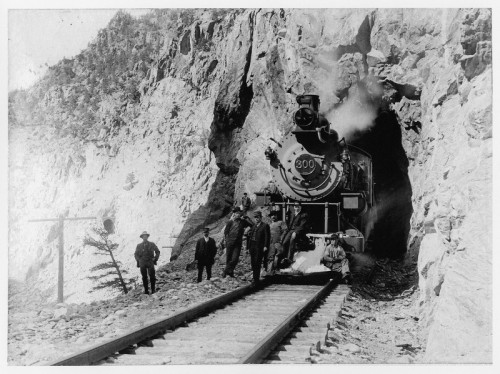

None of this was easy. They had to cross numerous arroyos filled with soft sand subject to summer floods and—most difficult of all—blast their way through Guadalupe Box Canyon, leaving the two tunnels we drive through today on Hwy. 290. That 3/8 mile cost $500,000, half the cost of the entire railroad.

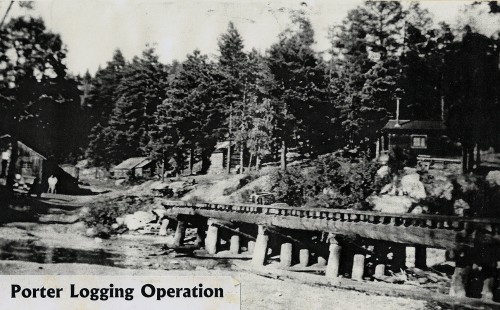

In 1921, the Jemez Land Company was sold to Guy Porter and his wife, Virginia, from Charleston, West Virginia. They were assisted by their two sons: Frank and Lyman, as well as other lumbermen from the Southeast. Details of land transfers and timber sales, as well as specifications on the railroad’s rolling stock, are ably reported in Vernon Glover’s book, Jemez Mountain Railroads. In 1922, the Porters incorporated as White Pine Lumber Company.

Raw and rough-cut timber was hauled to a sawmill in Bernalillo on the new Santa Fe Northwestern Railway. The 120,000-gallon water tower, which once stood adjacent to a 12-acre log pond, is still a highly visible landmark in Bernalillo. The route from Bernalillo required a bridge across the Rio Grande– no easy endeavor–and then crossed Santa Ana and Zia Pueblo lands. They met objections when they reached Jemez Pueblo and, after years of legal maneuvers, gained right of way by condemning a strip of land across the Pueblo on an order from the U.S Land Commission.

Construction continued on all branches of the SFWR throughout the following years. The first log train rolled out of the mountains to Bernalillo in 1930. From Bernalillo to Box Canyon took a little over three hours. About one hour of that was used up on the steep grade from Box Canyon to Porter. Besides Bernalillo, water was available at San Ysidro, Box Canyon, and Porter.

Look around on all the large mesas surrounding the Canon de San Diego and beyond to what is now the Valles Caldera. Signs of the busy logging industry of 100 years ago are visible in the large stumps that remain, the faint paths of old roads that crisscrossed every slope and mesa top, overgrown path of log chutes, and the bits of sheet metal and other debris left on the old logging camp sites. Go to this 2017 illustrated report by Thomas Swetnam for details of log chutes in an area north of Jemez Springs.

Major loading points on the Jemez branch were Canyon Landing, near today’s community of Cañon; Deer Creek Landing, one mile north of where the gate is now on Forest Road 376; Porter Landing at the junction where the Rio Cebolla and Rio de las Vacas join to form the Rio Guadalupe; and further north at O’Neill Landing on the Rio de las Vacas. From 1925-1937, at the height of the lumber business, the lumber camp at Porter grew to a town with a population of 300. It boasted a post office, company store, locomotive repair shop, and small lumber mill. Today all that remains is a falling-down stone chimney, a reminder of the grandest building in Porter—the superintendent’s house.

An article in El Cronicón, the Sandoval County Historical Society newsletter, December 2014, describes an early logging camp:

Logging camps typically lasted 2 years, and more than 130 structures have been found in Sandoval County. Often the workers lived in canvas tents, and sometimes in basic log cabins. They might use an old 55-gallon drum to make a stove to heat and cook on. They might eat canned food, or whatever they could carry up, and had little conveniences.

One of the camps with the luxury of cabins was located just south of the tunnels, named after William Gilman, one of several former steamship captains who came to work on the railroad and became a vice president of the SFNW. The cabins remain today as rental houses. Locals often refer to Guadalupe Canyon as Gilman Canyon. In the large flat area seen across Hwy 290 from Gilman Camp was Gilman Landing, renamed from Box Canyon Landing.

Smaller lumber operations were scattered throughout the mountains. One of these was a sawmill in Ponderosa operated by Lew Caldwell.

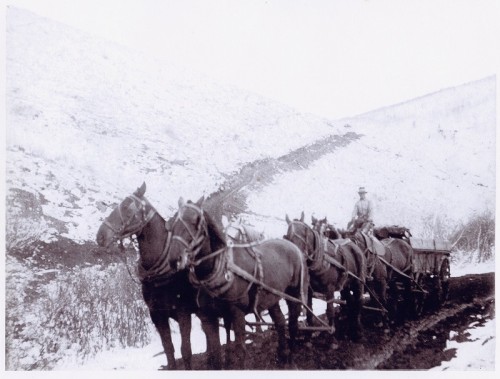

Logging in the early days was barely mechanized. The rail cars were, of course, pulled by steam locomotives, and roads were built using steam shovels. Cutting the large ponderosa trees was done by hand with crosscut saws. Timber was skidded with horses and mules. Reading between the lines in Glover’s book, it was a really big day in 1922 when the railroad acquired a diesel log loader that would run on rails.

Logging in the early days was barely mechanized. The rail cars were, of course, pulled by steam locomotives, and roads were built using steam shovels. Cutting the large ponderosa trees was done by hand with crosscut saws. Timber was skidded with horses and mules. Reading between the lines in Glover’s book, it was a really big day in 1922 when the railroad acquired a diesel log loader that would run on rails.

The lumber business went through several periods of boom and bust and finally began a slow downward spiral which ended in 1965. During the years of decline, rails for spur lines were pulled up as the areas they served were logged out. The big flood of 1941 took out miles of track and several of the large trestles. At that time, the railroad into Guadalupe Canyon was abandoned, and the track pulled up. The roadway and the tunnels were enlarged to accommodate logging trucks.

The railroad running toward Cuba was mostly oriented to the copper mines in that area. Eventually that track, too, was torn up. Remnants of the old railroad bed are still visible south of Cuba, as well as along the route through the Jemez Mountains.