A few huge ranches exist in New Mexico, and by huge, we mean tens of thousands of acres. One such tract of land sits right in the middle of the Jemez Mountains and is now the Valles Caldera National Preserve. Much has been written about this local landmark, so this overview will touch only the highlights. Kurt F. Anschuetz has written an exhaustive study of the land use history of the Valles Caldera titled More Than a Scenic Mountain Landscape. For an in-depth history, see Valle Grande: A History of the Baca Location No. 1 by Craig Martin. For the latest information on activities and access, go to the National Park Service page about VCNP.

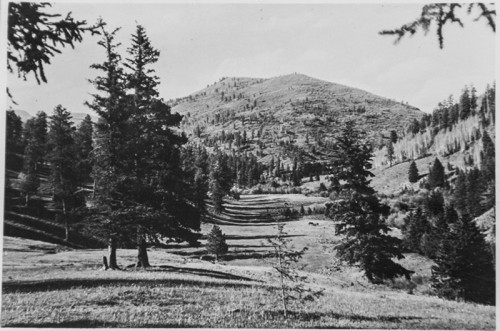

The Preserve encompasses most of a large volcanic crater left of eruptions that occurred millions of years ago. The most prominent feature is the Valle Grande, the largest of several grassland valleys inside the caldera. Satellite images and topo maps reveal the outline of the crater, 13.7 miles in diameter. After the eruptions, cinder cones built up in the crater, forming the peaks we see today, including Redondo Peak, which at 11,253’ is the highest point in the Jemez Mountains.

Since this area was first settled in the early 1800s, millions of cattle and sheep have been grazed there, and millions of yard feet of lumber have been hauled out. It has been the site of geothermal drilling and a sulphur mine. The headwaters of the East Fork and San Antonio creeks rise here. In the 1970s, when guided hunts were offered, it was a hunters’ paradise for those who were able to pay a hefty fee to hunt the trophy elk that regularly winter there.

Of course, all those involved in these various activities totally ignored the fact that the nearby pueblos, most especially Jemez, claimed the lush valleys and heavily timbered hills as part of their traditional homelands as well as part of their original Spanish land grant.

The first owner was Luis Maria Cabeza de Baca, who acquired the 90,000-acre property through a swap with the Las Vegas (NM) Land Grant in the late 1800s. For many years, the name used by locals in the Jemez was Baca Location No. 1. (See Land Grants for details.) Mariano Otero homesteaded in the area in1883 and bought Baca Location No. 1 in 1899. He also owned other property in the Jemez and had grand dreams of developing a resort in Jemez Springs. Otero had mining rights on the western boundary of the Baca, and built a mill and later a resort, with a stage line running from Santa Fe and on to Jemez Springs.

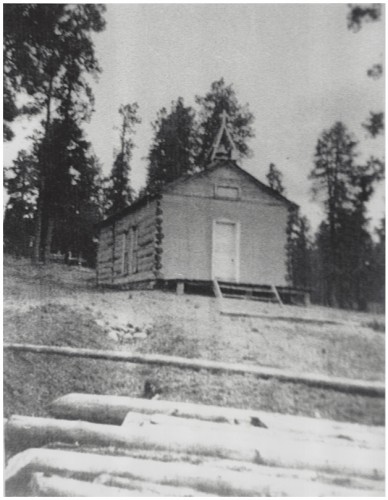

Frank Bond, a local merchant, and his brother George obtained grazing rights in 1917, and they purchased Baca Location No. 1 in 1926. At one time they had 30,000 sheep grazing there. In the 1950s, the focus shifted to cattle, and as many as 12,000 head grazed in the lush valleys. The Bond family built a number of log cabins on the ranch for foremen and their families. In 1959, the Bond family leased the ranch to Sam King from Texas, and their active involvement ceased.

Bond leased the timber rights, and the heaviest logging occurred in the 1930s although clear-cutting was not used until the 1960s. The New Mexico Lumber and Timber Co. was already logging in the Cañon de San Diego grant, and they expanded their operation into the southeast corner of the Baca.

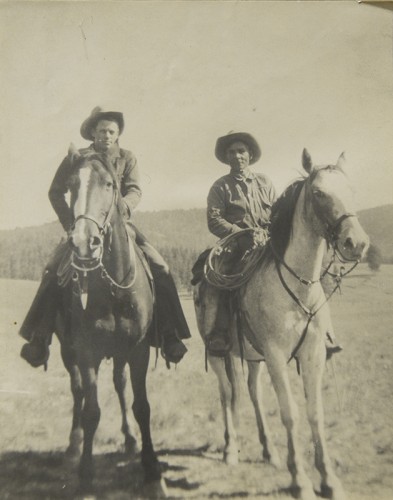

Over the years, the ranch employed many local people as sheepherders and cowboys. When raising sheep was the main focus, workers were nearly all Hispanic, coming from nearby communities such as Cuba, San Ysidro and Vallecitos in the Jemez, and Espanola, El Rito and others to the east. They worked on the partido system, something like share-cropping. Bond, the rico, would give the partidario a number of sheep, which were the sheepherder’s responsibility for the year. At the end of the year, the partidario would repay a certain number of sheep plus pledge a percentage of the wool. Since they assumed all risk of their flock and bought all supplies at the company store, the partidarios rarely came out ahead.

The last private owner was Pat Dunigan, a Texas rancher, who eventually bought the timber rights and reduced the logging and grazing, which did a lot to restore the watershed. He continued to permit limited grazing, fishing and hunting, all for a fee, from outside parties. (Some hunters were said to have paid as much as $10,000 for a trophy elk, and the resident elk herd numbers in the thousands.) He was also the first to rent space for Hollywood productions, and a number of well-known Westerns were filmed there. Sets of two movie locations that still stand today are on the visitor’s tour. Dunigan experimented with geothermal wells, but none were cost effective.

The idea to create a national park in the Jemez had been around for at least 50 years when negotiations began between the Dunigans and the federal government. When rumors circulated of a proposed ski resort and condominiums, the majority of local residents preferred it not fall into the hands of developers and campaigned for the park. They didn’t exactly get a park. Many legislators believed that too much of New Mexico was in federal land, so they devised the Valles Caldera National Preserve. The Preserve was to be self-sustaining and governed by a board of trustees that represented a variety of interests. While open to the public on a fee basis, the Preserve would continue to earn money from grazing, hunting, fishing and movie productions. The Preserve never was able to sustain itself and in 2015, the land became part of Bandelier National Park.