By Joe Wise, New Mexico Magazine, February 1998

In a narrow canyon at the end of a dirt road high on the wooded flank of the Jemez Mountains, three weathered buildings, struggling against time and gravity, mark the site of one of the boom-ing mining towns in New Mexico.

The three buildings, sun dried and baked the color of ginger-snaps, are all that is left of Bland, a once-prosperous town that in its heyday boasted a population of 3,000.

Founded in 1894 after several gold and silver claims were established in the area, the new town soon came to be known as Bland, named for Congressman and presidential nominee Richard Parks (Silver Dick) Bland of Missouri, whose Bland-Allison Act of 1878 helped prop up the falling price of silver.

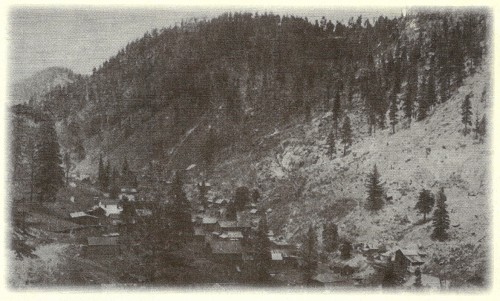

Miners from all over the Rockies poured into the area known as a “new Cripple Creek” and the scattered claims grew rapidly into a group of more than 50 mines. The town grew so fast it was said that a resident of the town, after two weeks absence, would not recognize it on his return. Four sawmills and 100 men working day and night couldn’t meet the demands for lumber, and additional building material had to be hauled in by stagecoach. In one four-month period alone, more than 50 houses and businesses were built.

At its peak, Bland had squeezed into its 60-foot-wide canyon, two banks, a hotel, the Bland Herald newspaper, an opera house and a stock exchange in addition to boarding houses, schools, saloons, gambling halls and a redlight district. There was some talk of building a church.

When the narrow canyon was filled with buildings, enterprising residents blasted and dug holes into the steep slopes to serve as platforms for their homes. One main street homeowner was forced to put his outhouse in front of his house because there wasn’t room for it elsewhere.

Electric power to run the mill to light the town was carried on 35 miles of power lines strung up the canyon from Madrid. Some of the old poles can still be seen in the canyon. Water was piped in from adjacent Medio Dia Canyon, so deep and narrow that the sun could be seen only at midday.

Over at Albermarle, Bland’s sister city, mines lined the main street. Ore was hauled over an electric tramway to a 175-ton-per-day stamp mill, the first all-steel structure in the state.

A three-and-a-half mile wagon road, known as The Teamsters Nightmare, linked the two towns across a high ridge. One section, where the rugged track climbed 1,500 feet in less than a mile, was the site of some spectacular accidents, with wagons and teams plunging into the canyon below.

The town boomed during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The first gold and silver strikes were assayed at $20 a ton. During Bland’s raucous career, ore valued at more than $1 million -$150 million in present-day money was taken from the nearby hillsides.

But in time, costs rose and the quality of the ore played out. The mines at Bland collapsed in 1903, along with the general decline of mining in the West. Few people stayed on. The Post Office closed in 1935, and by 1950, Bland was a ghost town.

As I walked from the gate up the hill to the townsite the only ghost I saw that day was the smiling Casper-like caretaker named Wayne, who lives there year-round.

“It’s a good thing I’m here,” he said as we walked the main street, “or they would carry the place off. Like they have done over at Albermarle. Nothing left there but the foundations. Once I found two guys up here with a moving van.”

We walked the hillsides above town, once clear cut for timber and firewood, now covered with 80 years of second-growth forest. Scattered through the woods, the stone foundations of houses, over– grown with pine and potentilla, lay in their rocky niches. We passed a cinnamon cabin, still stand-ing, but listing into the hillside that threatened it.

“A man named Hofheinz lived here,” Wayne said as we scrambled over the steep slopes. “He did all the stone work for the town.”

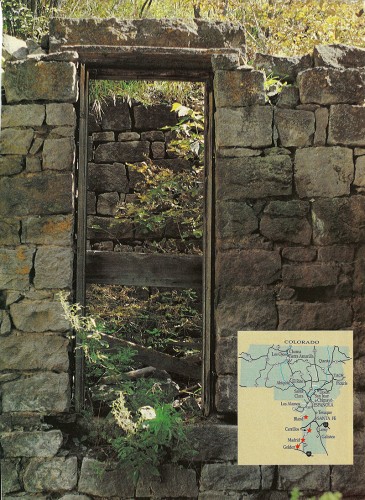

We looked into the roofless jail, cut into the hillside and lined with stone, the barred window still in place.

“The shackles were in here ’til a year or so ago,” Wayne said. “Til somebody stole ‘em.”

Along the main street, the site of the bakery is overgrown with oaks and underbrush. Dandelions bloom in the chinks of the closely fitted masonry of the storage room, the dark interior still cool in the summer afternoon. Next door, the two remaining stone walls of the bank, closed off with a cedar post fence, serve as a makeshift corral.

caretaker. Photo by Joe Wise.

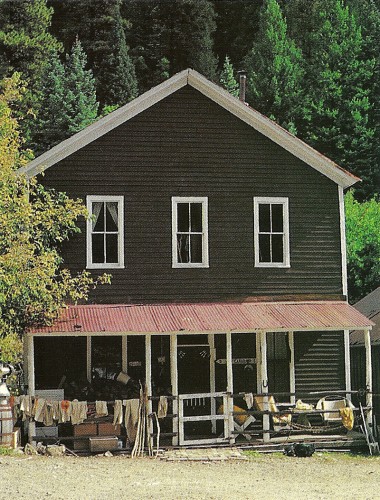

We walked across the street into the parlor of the Exchange Hotel. On a bookshelf, with back issues of the Bland Herald, is the original leather bound register:

Mrs. Thos. H. Benson, Prop.

Guests without baggage are required to pay in advance.

Behind the parlor is a dining room and a large kitchen with a twin-oven wood cookstove. Upstairs 13 wainscoted guest rooms with antique wooden bedsteads line the narrow hall.

The hotel opened on June 15,1899, and the first guest was Frank Botsford of San Diego. During the first two months, the hotel was host to 65 guests registered from Santa Fe, St. Louis, Chicago, New York, Washington D.C., Cripple Creek, Sonora, Mexico and British Guiana.

The saloon next to the hotel is filled with old books and magazines including the January 1911 issue of National Geographic, yellowed copies of The Graphic and Matilda Ziegler’s Braille Magazine for the blind. Makeshift shelves are lined with old bottles, purpled by time, and empty cans of Revelation Smoking Mixture (“It’s mild and mellow.”) and Embassy, ABC and Canadian Ace beer. A propane-fired Coldspot refrigerator hums in the back corner. (“It freezes everything.”)

On the other side of the hotel, at the double bay-windowed doctor’s house, the walls of the bedroom are papered with pictures from magazines and in the medicine chest are bottles of Salcicon tablets and a jar of Ben Gay, spelled the French way, Ben-Gue.

Sitting there on the hotel porch in the delicious cool sunshine awash in the perfume of the warm pine planking, I turned to Wayne.

“What’s the best thing about living up here?”

“Peace and quiet,” he said without hesitating.

“What’s the worst thing?”

“Winter. It’s a sixteen-mile round trip to the nearest store. That’s a long way to go on skis for a beer.”

Too bad, I thought. If it were 1889, he could have a beer at one of the dozen saloons in town.

As I drove down the canyon from the past toward the city, I stopped by the ruins of the old stamp mill, collapsed except for its rock chimney standing like a headstone. Nearby was the tunnel entrance to a small mine, where someone’s dreams soared and died.

Standing there in the quiet of the canyon, once filled with the sounds of hope and industry, I thought I could hear, as if it were real, the measured rhythmic song of the hammer and drill.