By Fritz Thompson, Albuquerque Journal Magazine, November 21, 1978

Effie Jenks is sitting in one of those austere dinette chairs, all chrome and vinyl, fretting about a missing bottom button on her blouse and trying to shield it from a photographer across the room. It is a warm autumn afternoon outside her sparsely furnished apartment in downtown Albuquerque, far removed from the two-room cabin high in the Jemez Mountains, where she was the one-time proprietor and only perpetual resident of a ghost town. It had been in this cabin that Effie could be her most effusive; dressed in a gray sweatshirt and tattered blue jeans with the knees torn out, sitting in a creaky rocking chair, surrounded by the paraphernalia of a lifetime and drinking Jack Daniels neat from a fruit jar.

Come January, she’ll be 81. She speaks with the faint trace of a British accent, the legacy of her Oxford-educated husband, a mustachioed gentleman whose framed portrait stands prominently atop a bookcase in Effie’s sitting room. He died in 1941 in a Denver hospital, setting in motion the events which brought his widow to endure and indeed relish the increasingly long periods of solitude in an abandoned mining town reached only by a rough and rocky road north from Cochiti in Sandoval County.

She emerged from those years in the mountains with her great good humor intact. She is an avowed ally of the underdog with a child-like laugh; an energetic and culture-wise lady who drinks her coffee out of a mug, not too hot “because I hate to just sit there and look at it while it cools.” She is engagingly gregarious, yet she openly detests gatherings that are phony exercises in social sophistication. There is a thin edge of sorrow when she talks about the dwindling number of her contemporaries, or about the death of her husband, or about how she sometimes feels very alone.

How she came to own “a whole slew” of played-out gold mines and all but one house in the empty town of Bland, N.M., is a circuitous story that began on the flat plains of South Dakota where Effie, at the age of 3, toddled off to school with an older sister. No one bothered to send her home and she became something of a prodigy as she advanced through the grades with children who were three years older. Before she was out of her teens, she had decided to become an actress or a writer, but her vision then was limited to unbroken miles of South Dakota wheat fields, rippling like a great golden sea into the horizon.

She remembers telling an uncle “I had decided to be a writer and that I was going out to see what the world was about. I didn’t know anything – all I knew was waving wheat fields and pulling weeds in my mother’s garden and a few little odds and ends. I knew nothing about the world, so what was I going to write? I had spent all my life in South Dakota, but it wasn’t my idea of what I wanted.” . . . She eventually headed farther West. She was still a very young woman when she landed a job as manager of the dining hall at the now-defunct Sun Mount Tuberculosis Sanitorium near Santa Fe. It seemed like a good idea at the time, but it was more than that; it was a propitious move and it changed forever the course of Effie’s life. . . .

Effie trekked south to the University of Nebraska. Although she ultimately put in four years at the school, she never received a degree because – to use her favorite expression – “I was interested in all manner of things.” She registered for a course in forestry, the first female to do so, and would have signed up to learn how to fly a plane (“When I was young I had all manner of courage”) if she had been able to scrape up the fee. She took classes in botany, pottery-making, elocution, teaching, sociology, German and Spanish. . . .

Effie indeed learned about life. She learned it in the abandoned gold and silver mines, where she worked by herself to shovel up the slag and push the rail-riding ore cars through the tunnels. She learned it in the practiced elegance of a Harvey Girl, the preferred waitress for Igor Stravinsky, the Santa Fe Railway brass and scores of more common folk. She once traipsed over a mountain, alone and in the dark, to fight a forest fire.

My father had done pretty well and I told myself I was only there to learn about life. Anyway, I remember when I got into the uniform I was terribly embarrassed and I hesitated before going into the dining room.”

The job was not nearly so demeaning as she had envisioned. “I got over it, believe me,” she admits. “I don’t feel that way about it now – it’s a great position. I got along very well. In those days, the Harvey Girls were very high-class girls.”

“Anyway, I met some of the most wonderful people on earth and I waited on one president, (Lyndon Johnson, but it was before he assumed the office), various movie stars, and a great many educated people. I soon got to like being a waitress, and I have always liked it. If I wasn’t so darn old, “ she laughs, “I’d just as soon go back.”

The country fought through the Depression, weathered a world war, mourned an assassinated president, stumbled through the tumultuous 1960-70 turn-of-the-decade and burst into the space age during Effie’s tenure as a Harvey Girl.

Drawing on her own fierce dignity, she dealt with each situation as it arose. When the stock market crashed in 1929, it nearly wiped out her father back in South Dakota. Although her own salary was cut from $45 to $40 a month (with room and board), Effie felt compelled to send money home. “I decided the Depression was really an historical event we were going through,” she says, “and I decided that in the years to come I would be asking myself, ‘What did I do for people during the Depression?’ So I sent my father money, and I helped many people in different ways. I came out of the Depression just as poor as the people who hadn’t any job, because I had given away everything I made. I’m no sorry. I’m a little bit proud of it.

Still, Effie was not blind to changing fashion and the loosening mood of America. In that era, it was surely considered a brazen act when Effie openly defied company policy by announcing she was going to have her hair bobbed, in keeping with the forthcoming style. Anyone arriving at work with a bobbed hairdo, she was warned, was subject to immediate dismissal. With three other waitresses as allies, she went to the barber’s and returned to work the next day. The manager evidently backed down – not a word was said.

During World War II, Effie was troop train hostess, in charge of handling the meals for the massive number of troops crossing the country. And when the managers of the Harvey chain gathered at the Alvarado, Effie was assigned as waitress for their private dining room. One of her friends asked her if the honor did not produce big tips, but another answered the question: “She’s lucky,” the second waitress said, “if she doesn’t get hell.”

Because of their uniform good looks, because of their virtue, because of their elegance, and because of their inherent charisma, the Harvey Girls were first choice among eligible men.

“There were always a lot of men asking for dates,” Effie says, “and once in a very great while, after I’d known someone for a long time, I used to go out on dates. After I got older I went oftener. I found men are pretty decent if they know they have to be.”

Predictably, Effie met her husband, Harry, while waiting tables at the Alvarado. It was not exactly love at first sight; he was married at the time.

“I waited on him and his first wife for a number of years, and then his first wife went on a Cook’s tour and she died while they were in England. I never in the world thought of marrying him then. It was five years before I began to think he was pretty darn nice man, and about the same time I thought it was time for me to get married, if I was ever going to have any children, because I like children. So I smiled at the boys, and I had six volunteers, believe it or not. But I decided my husband was the best, and I told him he’d have to live up to it.

“We didn’t have any children, and with the world what it is today, I don’t think you’re doing them any favor by bringing them in on all this trouble.”

Thomas Harry Jenks was a mining engineer. After their marriage in 1936, the first place he took his bride was to Bland, where he had a lease and option on most of the properties. They stayed at the Exchange Hotel. But he spent the next five years of their married life managing mines in Central City, Colo., and except for the summer of 1938, which they spent in Bland, the couple resided in Denver.

Harry Jenks became ill in early 1941. Effie knew there was something wrong. “I took him to the doctor in Denver, and I told him if he found anything serious, “Don’t tell Harry, tell me.” Harry was hospitalized, and the doctor told Effie, “He’ll never get up from that bed and he’ll never get any better.” He had suffered a cerebral stroke.

He was unconscious. When we knew it wasn’t going to be much longer, I stood beside the bed and held his hand. A nurse told me he didn’t know I was there. But I said, “ He may not know I am here but he always knew I would be here.”

Momentarily cast adrift, Effie did not waste a lot of time deciding what to do. She wanted to move to Bland. She had always loved the canyon, and it was the site of a happier time in her life.

“After my husband died and they shut down the mines, I felt pretty low,” she says. “I had to reason myself out of it. I made up my mind I had to do the best I could. It takes quite a long time to get over the loss of someone you love, and it was that, more than the loneliness. I had decided that I was going to be brave and that I was not going to cry and I was not going to break down. Anyway there was so much work to be done, and I immediately set about to repair the road. But one day I sat down on a rock, and I was feeling very low. The shortest verse in the Bible came to my mind – “Jesus wept”- and I decided if He could cry, then I could, too. And it all came out, in all the tears, and I imagine you could hear it from one end of the canyon to the other. But they say time is the great healer.”

With her accumulating properties in Bland, Effie was convinced she had to go back to work “to pay the taxes.” She tried the Alvarado again, but they had no openings and they sent her to La Fonda in Santa Fe. For the next several years, she worked there in the winters and spent her summers in Bland. She frequently asked for time off from her job so she could attend to her property and the threat of theft was a constant worry.

Bland was a totally abandoned mining town when she learned a considered chunk of it was for sale in bankruptcy proceedings. She says she was originally hoodwinked in her not-too-enthusiastic inquiries. After she learned the truth of the proceedings, she became downright indignant and tenaciously involved in a complex battle over the purchase. She flew to New York to deal directly with the owner, righteously incensed at all the finagling. In the end, she became the sole owner of the town and all but 1 1⁄2 of the defunct gold and silver mines.

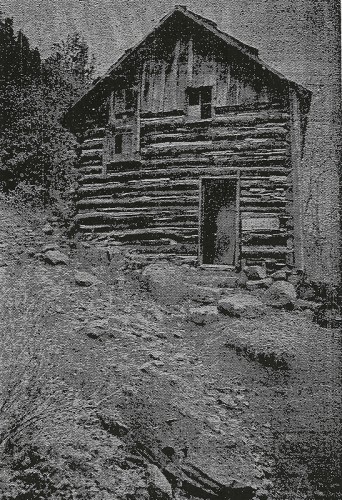

The property amounted to less than a dozen houses, the 12-room Exchange Hotel, the mills, a number of barns, and numerous and sundry antiques.

“After I got back to Bland, you just couldn’t get me out of there,” she says.

Now and then, as the years passed, smaller parcels of the ghost town came up for sale, and Effie bought them. She came to own the Crownpoint Boarding House, the huge mill – sheathed in corrugated metal – the broken and twisted ore car rails, the pump house, the log cabins and shanties and outhouses that line the narrow canyon for at least a mile, climbing from an altitude of 7,400 feet at the lower end of town to more than 7,600 feet up at the boarding house.

“I never had any intention of buying property when I moved up here,” Effie says. “But everything began to be for sale, and that’s when I began buying the property.”

She moved into a rambling, three-bedroom log house that once served as a ranger station. She saved it from being burned to the ground, on orders from the structure’s legal owner, the Forest Service, when she argued that she could maintain the property and would lease it from the agency. She called in carpenters and had the building jacked up and strengthened, with a new floor and stronger beams.

During her more than 30 years in the canyon, Effie lived without electricity, running water, natural gas and, most of the time, a telephone. She has a Jeep but has never had a driver’s license.

Eventually, Effie came to own 380 acres of property in Bland and Colle Canyons. She thinks there were about 85 mines dotting her land, none of them in production. “I don’t really know how many mines I had, but it was an awful lot of them,” she says.

She became increasingly worried about thievery, and she was fearful of “someone who might think I have some gold bricks hidden away here and would come in and knock me over the head to get it. I don’t have any gold bricks.”

In the last six years, Effie has sold most of the ghost town, keeping only the weather-beaten house next door to the two-story hotel. The majority of the canyon is now in private ownership, and it is closed to the public, with a padlocked gate to the premises.

On a recent visit to the canyon, Effie found her house dark and silent, the rocking chair with a thin film of dust. This time, Effie was dressed in a stylish pants outfit. She rummaged around in a storeroom, looking for a particular piece of memorabilia. “I’ve got to come up here and clean this place up,” she says. “So much stuff…”

Thus it was not the loneliness, not the solitude, not the absence of ordinary conveniences that drove Effie from Bland. Quite the contrary, it was outside forces, theft and vandalism – perhaps the very things she had sought to escape – which drove her back to the city.

Effie found a religion and a reverence in the mountains. She is not, and never has been, the church-going type. “My parents were very honest and very kind and very charitable,” she says, “but they never considered going to church.”

“My husband was a devout Episcopalian. Before we were married, I told him I couldn’t join the church, and he understood that. I told him if we had any children, I had no objection at all to have them raised in the Episcopal faith. He went to church every Sunday, and I went with him.”

“I don’t think there is any church I could join. But I do believe there is a great universal mind, and all of us have a part of that universal mind in us. It’s not some whiskered man like in the pictures. I can worship my kind of god, but my god doesn’t want me to kneel, my god wants me to stand up straight and look up.”

When it comes to choosing up sides, Effie has always cast her lot with the downtrodden, the poor and the distraught. As a 4-year-old in the second grade, she says, she sided with a little girl who was being taunted because she had scarlet fever. “Of course, I came down with scarlet fever, but that didn’t discourage me,” she says.

When she was 5, she bluffed a gang of young bullies and won. “Two little girls went to the privy and a bunch of boys started throwing rocks, making an awful racket against the sides and roof. The little girls were scared and afraid to come out. I felt sorry for them, and I announced I was going to take them to the house. I marched down there, took them by the hand, and led them to the house. Not a stone was thrown.”

“Very early in life, I had a feeling for the underdog, and it has continued,” Effie muses. “Sometimes, I wonder if I have taken on too much responsibility. Some time ago I decided I’ve done my share, I’m not going to do anymore for anybody. But then I catch myself violating that rule…”

Two cats, Lady B and Rocky Boy, are among her most valued ties to Bland. After having a free run of a mountain canyon, the cats are fidgety and restless in the Albuquerque apartment.

Effie brews another cup of coffee, serves it without a drop sloshing into the saucer. Her waitress hand is as steady as ever. She looks wistfully out the window. “I’ve seen a good deal of trouble, and at the age of 80 you begin to lose your

contemporaries. I feel very alone sometimes.” Then her indomitable will brightens.